Art in the Aftershocks: How Earthquake Legends Inspired Japanese Catfish Prints

We examine the origins of Namazu-e, a unique form of Japanese art inspired by earthquake folklore. These prints feature the giant catfish Namazu, believed to cause earthquakes, and show they reflect societal fears and beliefs of the people of Edo, as well as illustrate how myths and natural disasters shaped artistic expression of the era.

When engulfed by untold calamities, human beings tend to ascribe meaning to the madness. The people of Edo, ravaged by the Ansei Edo earthquake (1855), were no strangers to this phenomenon. Just two days after the devastating earthquake, the first hastily-produced namazu-e or catfish prints began circulating.

Namazu-e are Japanese woodblock prints depicting a gigantic catfish (a namazu) who is said to be living at the kaname-ishi (the “foundation stone” in mythology that holds down the Japanese archipelago). When left to its own devices, the namazu thrashes about and causes earthquakes. The god of thunder Kashima (or Takemikazuchi) is responsible for subduing the namazu with the foundation stone. When he lets his guard down, the namazu moves and subsequently causes earthquakes.

Namazu-e prints provide us with a peek into the psyche of a country on the precipice of unprecedented change, often expressing thinly-veiled political or social commentary with the catfish imagery.

The 1855 Ansei Edo Earthquake was only the latest in a string of calamities to befall the people of Tokugawa Japan. From the 1830s, persistent natural disaster struck the country bringing famine, epidemics, and earthquakes. These were coupled with social and political turmoil such as uprisings, revolts, and other notable events like the Perry Expedition.

A prevailing belief of the time, rooted in Confucianism, was the existence of cosmic forces that intervene to rectify errant human societies. Many believed that the state of the Tokugawa government had become increasingly incongruent with the moral principles of the cosmos, self-evident from the decades-long chain of misfortunes.

The people of Edo experienced the earthquake in the context of this escalating chaos, seen as yet another manifestation of divine discontent. Even high-ranking officials were not impervious to such conclusions; daimyō Matsudaira Shungaku wrote in a memo to Abe Masahiro, the chief councilor of the shōgunate, that these events “definitely constitute a heavenly warning”. Namazu-e prints encapsulated these ideas through their illustrations, often accompanied by commentary spanning issues Edo residents saw unfolding before themselves everyday.

Curiously, the namazu has been associated with all sorts of earth-shaking events, not just earthquakes. The visits by Commodore Matthew Perry were seen by Edo residents with at best a momentary intrigue; however they left many government officials deeply perturbed. In 1853, Utagawa Kuniyoshi depicted this in a set of illustrations. One scene showed a monkey unsuccessfully trying to pin down a namazu with a bottle gourd, signifying the inability of the shōgunate to contain the hysteria unraveled by Perry’s visit. Another print, from 1855, portrays a tug of war between a namazu and Commodore Perry, with the namazu gaining an edge. The text alludes to an 1854 incident where a Russian warship, amidst negotiations for a trade agreement, was damaged by a tsunami caused by two earthquakes.

Reflecting Sentiments

Namazu-e reflected the public sentiment at the time. Prints produced within the first two weeks of the earthquake captured “fear, disgust, and anger”. Some initial prints purported to have talismanic abilities, serving as o-mamori (talisman). An example is the work titled Jishin o-mamori or Protection Against Earthquakes. It features Kashima and his deity subduing a namazu, accompanied by religious script and a depiction of the Big Dipper constellation, thought to be lucky. The early prints mirrored the fear of the people of Edo and tended to appeal to the deities, courting them for protection against further harm.

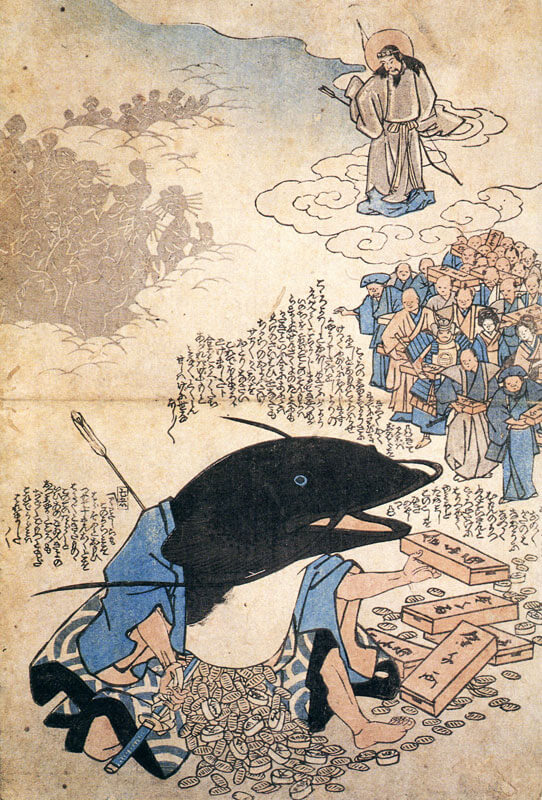

Other prints, however, expressed contempt at the deities for their botched handling of the disaster. One such derisive namazu-e is known as Namazu to kaname-ishi (or Catfish and the Keystone), published anonymously in 1855. The print depicts a menacing namazu wrecking havoc while Ebisu, a deity deputized by Kashima, dozes against the foundation stone. Another deity appears to be “thunder farting”, emitting drums out of his posterior (a reference to the peculiar pastime in Tokugawa Edo). Kashima is seen on horseback, arriving too late to prevent the chaos. Gold coins seem to be falling out of the namazu’s mouth, symbolizing a redistribution of wealth or perhaps a windfall for those who benefited from the earthquake. In stark contrast with other namazu-e that seek the protection of the deities, these prints exhibit contempt at their incompetence in allowing such an event to happen.

Namazu-e also depicted the anger of the people. In Subdued Catfish, a crowd pummels a giant namazu. Several distinct characters can be observed: Kashima, a courtesan, merchants, and a ghost of a earthquake are subduing the namazu. However, two people are observed attempting to pacify the crowd; they are workers in the construction trades. One of them, identified as a carpenter by his jacket's inscription, is himself being attacked by a charred, skeletal man who died in the fires caused by the earthquake. Namazu-e became a medium to satirize elements of society, including those who “profiteered” from the destruction of the earthquake.

The early prints were successful because they succinctly mirrored the instinctual reactions of the people of Edo. Suffering from loss, rebuilding their livelihoods, and faced with the residual psychological trauma from the aftermath of the earthquake, many related to the visceral emotions depicted in the initial namazu-e works. Others sought protection of the deities, pasting namazu-e on their roofs to act as o-mamori to ward off future damage.

Capturing Nuances

Later prints attempted to capture the nuances of post-earthquake Edo. When the dust had settled, it became clear that the earthquake had not been a universal tragedy. Drunkenness after Namazu the Great Catfish illustrates members of twenty five professions, some “smiling” while others “weeping”. People in the smiling group included construction tradesmen, physicians, and prostitutes, while those in the weeping group were merchants and entertainers. New economic opportunities emerged following the earthquake, but they could only be capitalized on if one had the right skills.

People also increasingly regarded the namazu as a divine antidote to the cosmic imbalance. After the mounting disasters, the belief that there was a need for yonaoshi or “world renewal” had picked up steam across Tokugawa Japan. Many in Edo felt that the wealthy were hoarding their wealth or otherwise manipulating the prices of goods, contributing to stagnation and inflation. Consequently, the destruction spawned by the earthquake was a boon for many of those who survived it. The money that was previously stashed by the rich was now flowing into the hands of the ordinary people. Yonaoshi namazu no nasake showed the usually destructive catfish in a benevolent role, rescuing individuals from the debris of destroyed structures.

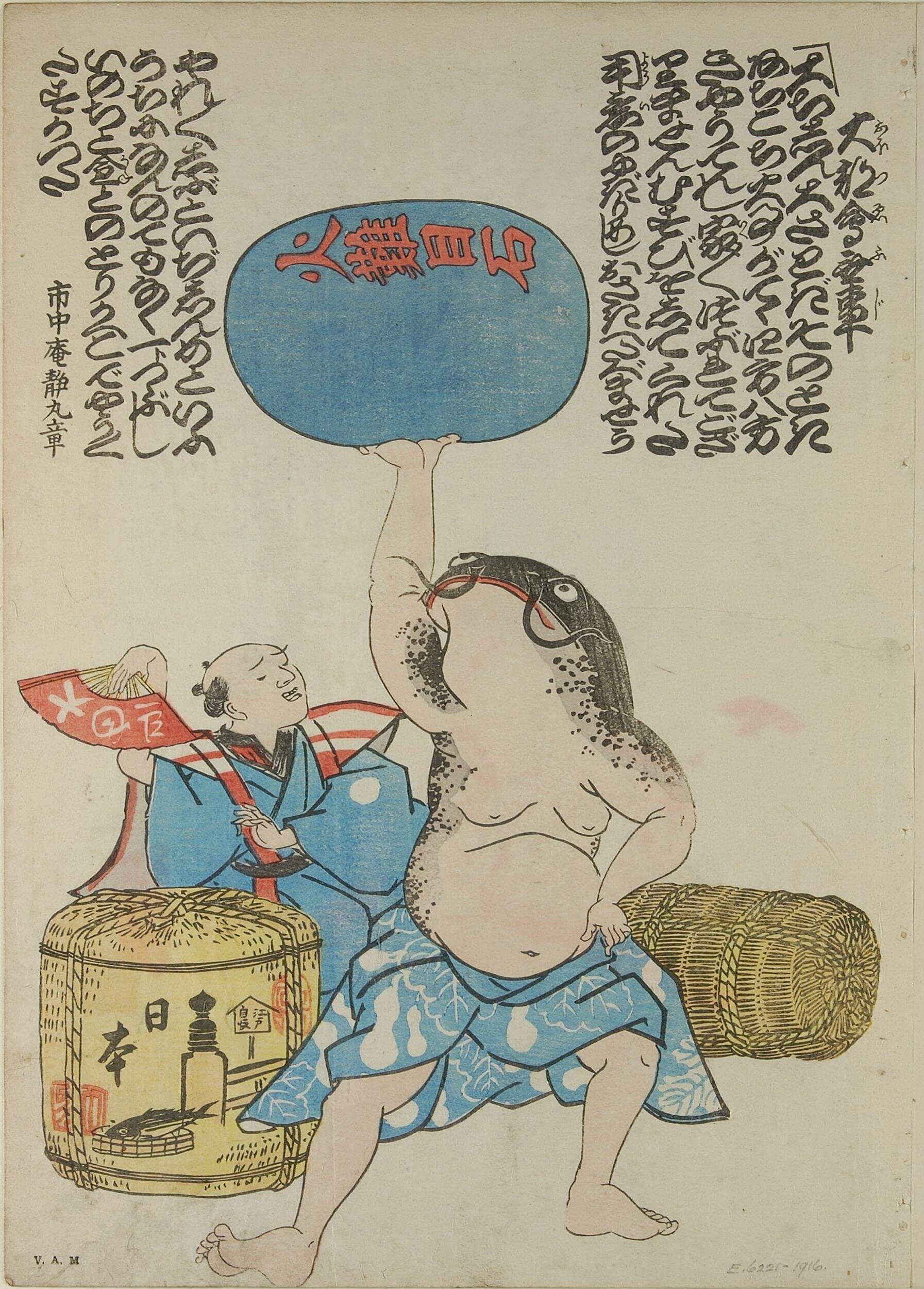

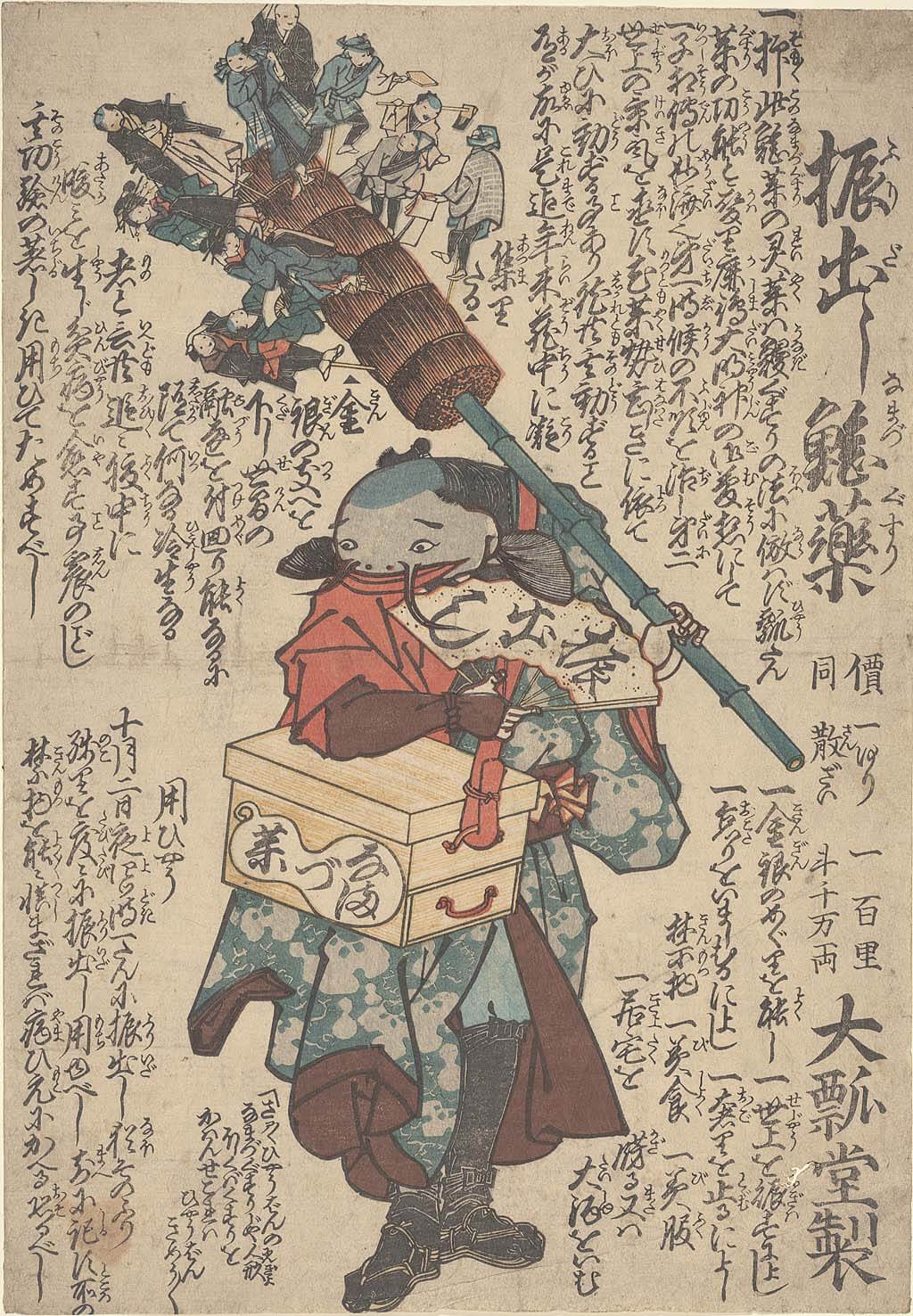

Another print, Furidashi namazu gusuri depicts a namazu dressed as a furidashi medicine salesman. Furidashi typically referred to a type of powdered medicine sold in pouches; it was mixed into hot water and consumed like tea. Rather than carrying the medicine pouches, the namazu has figures representing various professions that would gain from the earthquake. The text elaborates on the healing powers of this 'namazu medicine,' which include reactivating the flow of stored wealth, rekindling compassion, curing poverty, reducing laziness, and curbing the downsides of extravagant living. The extent of the prosperity enjoyed by the masses spawned numerous prints on the theme.

Each attempted a novel angle to illustrate this: in Seppuku namazu, a namazu commits ritual suicide, releasing gold coins from its stomach, and Hanjō takarabune presents a namazu-shaped ship loaded with money, carrying the Seven Deities of Good Fortune dressed in the attire of professions that prospered following the earthquake.

Threatening the Shōgunate

Over time, the populace became ambivalent. While the lower classes did not escape the earthquake’s repercussions, the primary burden of destruction fell on the upper classes. The area around Edo Castle where many prominent samurai lived was formerly known as the Hibiya Inlet of Edo Bay. In 1590, Tokugawa Ieyasu started reclaiming the tidal marshes. By 1855, these low-lying areas served as the primary neighborhood of samurai residences, which housed the bakufu’s closest allies among the domain lords, leading officials, and key offices. The earthquake devastated the structures here.

On the other hand, the commoner settlements across the moat on firmer ground, suffered minimal damage. This striking disparity contributed to the eventual mild callousness seen in later namazu-e works.

Another factor that may have fueled the proliferation of namazu-e was the anonymity of its creators and publishers. While nowhere as biting as fushiga prints (a genre of ukiyo-e dedicated to satire), many namazu-e were wrapped in social or political commentary. The strict censorship regime of the bakufu did not hesitate to penalize those behind fushiga prints, including arresting or fining many publishers and noted illustrators like Utagawa Kuniyoshi. The unsigned namazu-e allowed their creators to express themselves more freely, basing their works on sensitive topics and targeting powerful officials and groups. This anonymity allowed these illustrators to largely escape the consequences of their work.

The earthquake had thrown the government into disarray. Officials grappled with significant damage to their facilities and struggled to effectively administer the city. Capitalizing on the chaos, the publishers of namazu-e evaded censorship, as evidenced by the lack of a censor’s seal on any of the catfish prints.

Considering the political implications of the earthquake, the bakufu felt great unease by the proliferation of the namazu-e. These prints were not a mere reflection of reality, but a platform to critique society and express visions for an alternative. Although they never directly challenged the bakufu, the prints questioned the prevailing political and social systems.

It is no wonder that the continued circulation of namazu-e was seen as a threat.

The bakufu moved to ban namazu-e production. The publishing guild, reluctant to forego the profits from these prints, delayed enforcing the ban. Nevertheless, with the bakufu’s increasing intimidation tactics, including jailing nine guild officials, all namazu-e printing blocks were destroyed. Just two months after they appeared, namazu-e were banned.

End of the Aftershocks, Beginning of the End

However shortlived, namazu-e fulfilled many roles. They not only offered Edo's weary residents reassurance against future harm but may have also contributed to the shifting the winds in favor of the Meiji Restoration. Despite their fleeting presence, these prints have been recorded in the annals of Japanese history as crucial cultural elements in a nation on the verge of remarkable change.

Sources:

- Chronicles, Illustrations. n.d. “When Giant Catfish Shook The Earth: The Namazu-e Prints.” Accessed May 28, 2024. https://illustrationchronicles.com/when-giant-catfish-shook-the-earth-the-namazu-e-prints.

- Figal, Gerald. n.d. “Furidashi Namazu-Gusuri .” Accessed May 28, 2024. http://figal-sensei.org/hist157/Textbook/graphics/ch8/18.htm.

- Hanjō Takarabune (Treasure Ship with Deities Representing Those Who Made Profits after the Earthquake). n.d. Edo-Tokyo Museum. https://museumcollection.tokyo/en/works/6570355/

- Miyata, Noboru, and Mamoru Takada. 1995. Namazue : Shinsai to Nihon Bunka.

- Smits, Gregory. 2006. “Shaking up Japan: Edo Society and the 1855 Catfish Picture Prints,” Journal of Social History 39, 39 (4): 1045–78.

- Smits, Gregory. 2013. Seismic Japan; The Long History and Continuing Legacy of the Ansei Edo Earthquake. University of Hawai’i Press, 24-25, 89, 94-95. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvsrgqq.

- Utagawa, Kuniyoshi. 1853. Miraculous Paintings by Ukiyo Matabei (Ukiyo Matabei Meiga Kitoku) . Woodblock print on paper. William Sturgis Bigelow Collection. https://collections.mfa.org/objects/209685.

- 昭新 矢昌. 2002. “天道思想の変容,” 佛大社会学、 37. https://archives.bukkyo-u.ac.jp/rp-contents/BS/0027/BS00270L035.pdf.

- 野口 武彦. 2004. 安政江戸地震. 筑摩書房. https://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA6997150X.

- 阿部 安成. 2000. “鯰絵の上のアマテラス,” 思想 912、 (June): 46–47.